The antiderivatives of many functions either cannot be expressed or cannot be expressed easily in closed form (that is, in terms of known functions). Consequently, rather than evaluate definite integrals of these functions directly, we resort to various techniques of numerical integration to approximate their values. In this section we explore several of these techniques. In addition, we examine the process of estimating the error in using these techniques.

Earlier in this text we defined the definite integral of a function over an interval as the limit of Riemann sums. In general, any Riemann sum of a function \( f(x)\) over an interval \([a,b]\) may be viewed as an estimate of \(\displaystyle ∫^b_af(x)\,dx\). Recall that a Riemann sum of a function \( f(x)\) over an interval \( [a,b]\) is obtained by selecting a partition \[ P=\,\quad \text\quad a=x_0,\quad \text\quad x_≤x^*_i≤x_i \quad \text \, i.\nonumber\] The Riemann sum corresponding to the partition \( P\) and the set \( S\) is given by \(\displaystyle n\sum^n_f(x^*_i)Δx_i\), where \( Δx_i=x_i−x_,\) the length of the \( i^>\) subinterval. The midpoint rule for estimating a definite integral uses a Riemann sum with subintervals of equal width and the midpoints, \( m_i\), of each subinterval in place of \( x^*_i\). Formally, we state a theorem regarding the convergence of the midpoint rule as follows.

The Midpoint Rule Assume that \( f(x)\) is continuous on \([a,b]\). Let \( n\) be a positive integer and \( Δx=\dfrac

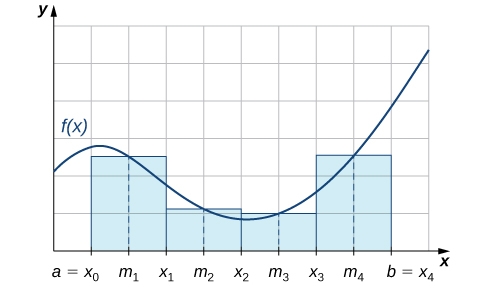

As we can see in Figure, if \( f(x)≥0\) over \( [a,b]\), then \(\displaystyle \sum^n_

Example \(\PageIndex<1>\): Using the Midpoint Rule with \(M_4\) Use the midpoint rule to estimate \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^2\,dx\) using four subintervals. Compare the result with the actual value of this integral. Solution: Each subinterval has length \( Δx=\dfrac=\dfrac<1>.\) Therefore, the subintervals consist of \[\left[0,\tfrac<1>\right],\,\left[\tfrac<1>,\tfrac<1>\right],\,\left[\tfrac<1>,\tfrac\right],\, \text\, \left[\tfrac,1\right].\nonumber\] The midpoints of these subintervals are \(\left\,\,\frac,\,\frac,\, \frac\right\>.\) Thus, \(M_4=\frac<1>\cdot f\left(\frac<1>\right)+\frac<1>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)+\frac<1>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)+\frac<1>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)=\frac<1>⋅\frac<1>+\frac<1>⋅\frac+\frac<1>⋅\frac+\frac<1>⋅\frac=\frac.\) Since \[ ∫^1_0x^2\,dx=\frac<1>,\nonumber\] the error in this approximation is: \(\left\lvert\dfrac<1>−\dfrac\right\rvert=\dfrac<1>≈0.0052,\) and we see that the midpoint rule produces an estimate that is somewhat close to the actual value of the definite integral.

Example \(\PageIndex<2>\): Using the Midpoint Rule with \(M_6\) Use \(M_6\) to estimate the length of the curve \(y=\frac<2>x^2\) on \([1,4]\). Solution: The length of \(y=\frac<2>x^2\) on \([1,4]\) is \[s = ∫^4_1\sqrt<1+\left(\frac\right)^2>\,dx.\nonumber\] Since \(\dfrac=x\), this integral becomes \(\displaystyle ∫^4_1\sqrt\,dx.\) If \([1,4]\) is divided into six subintervals, then each subinterval has length \(Δx=\dfrac=\dfrac<2>\) and the midpoints of the subintervals are \(\left\,\frac,\frac,\frac,\frac,\frac\right\>\). If we set \(f(x)=\sqrt\), \(M_6=\tfrac<2>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)+\tfrac<2>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)+\frac<2>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)+\frac<2>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)+\frac<2>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)+\frac<2>\cdot f\left(\frac\right)\) \(≈\frac<2>(1.6008+2.0156+2.4622+2.9262+3.4004+3.8810)=8.1431\) units.

Exercise \(\PageIndex<1>\) Use the midpoint rule with \( n=2\) to estimate \(\displaystyle ∫^2_1\frac<1>\,dx.\) Hint \( Δx=\frac<1>, \quad m_1=\frac,\quad \text \quad m_2=\frac.\) Answer \(\dfrac\)

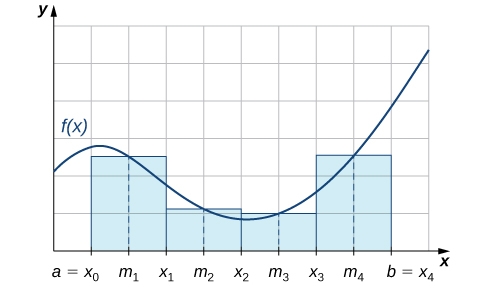

We can also approximate the value of a definite integral by using trapezoids rather than rectangles. In Figure \(\PageIndex<2>\), the area beneath the curve is approximated by trapezoids rather than by rectangles. The trapezoidal rule for estimating definite integrals uses trapezoids rather than rectangles to approximate the area under a curve. To gain insight into the final form of the rule, consider the trapezoids shown in Figure \(\PageIndex<2>\). We assume that the length of each subinterval is given by \(Δx\). First, recall that the area of a trapezoid with a height of \(h\) and bases of length \(b_1\) and \(b_2\) is given by \(\text=\frac<2>h(b_1+b_2)\). We see that the first trapezoid has a height \(Δx\) and parallel bases of length \( f(x_0)\) and \( f(x_1)\). Thus, the area of the first trapezoid in Figure \(\PageIndex<2>\) is \[ \frac<2>Δx\big(f(x_0)+f(x_1)\big).\nonumber\] The areas of the remaining three trapezoids are \(\dfrac<2>Δx\big(f(x_1)+f(x_2)\big),\, \dfrac<2>Δx\big(f(x_2)+f(x_3)\big),\) and \( \dfrac<2>Δx\big(f(x_3)+f(x_4)\big).\) Consequently, \[∫^b_af(x)\,dx≈\frac<2>Δx\big(f(x_0)+f(x_1)\big)+\frac<2>Δx\big(f(x_1)+f(x_2)\big)+\frac<2>Δx\big(f(x_2)+f(x_3)\big)+\frac<2>Δx\big(f(x_3)+f(x_4)\big).\nonumber\] After taking out a common factor of \(\frac<2>Δx\) and combining like terms, we have \[ ∫^b_af(x)\,dx≈\frac<2>\big(f(x_0)+2\,f(x_1)+2\,f(x_2)+2\,f(x_3)+f(x_4)\big).\nonumber\] Generalizing, we formally state the following rule.

The Trapezoidal Rule Assume that \(f(x)\) is continuous over \([a,b]\). Let \(n\) be a positive integer and \(Δx=\dfrac

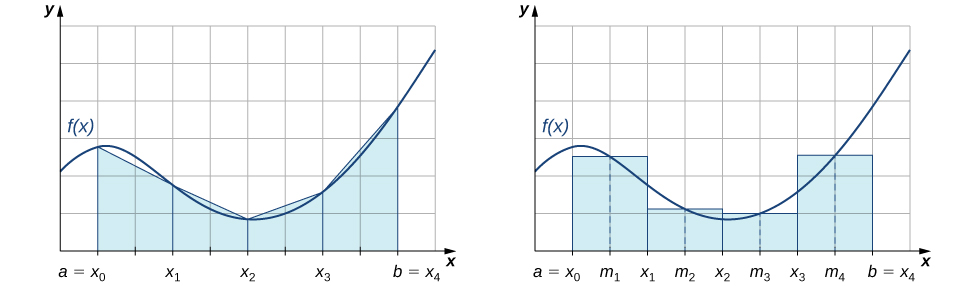

Before continuing, let’s make a few observations about the trapezoidal rule. First of all, it is useful to note that \(T_n=\dfrac<1>(L_n+R_n)\) where \(\displaystyle L_n=\sum_^nf(x_)Δx\) and \(\displaystyle R_n=\sum_^nf(x_i)Δx.\) That is, \(L_n\) and \(R_n\) approximate the integral using the left-hand and right-hand endpoints of each subinterval, respectively. In addition, a careful examination of Figure \(\PageIndex\) leads us to make the following observations about using the trapezoidal rules and midpoint rules to estimate the definite integral of a nonnegative function. The trapezoidal rule tends to overestimate the value of a definite integral systematically over intervals where the function is concave up and to underestimate the value of a definite integral systematically over intervals where the function is concave down. On the other hand, the midpoint rule tends to average out these errors somewhat by partially overestimating and partially underestimating the value of the definite integral over these same types of intervals. This leads us to hypothesize that, in general, the midpoint rule tends to be more accurate than the trapezoidal rule.

Example \(\PageIndex<3>\): Using the Trapezoidal Rule Use the trapezoidal rule to estimate \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^2\,dx\) using four subintervals. Solution The endpoints of the subintervals consist of elements of the set \(P=\left\,\, \frac,\, \frac<3>,1\right\>\) and \(Δx=\frac=\frac.\) Thus, \[\begin ∫^1_0x^2dx&≈\frac⋅\frac\big(f(0)+2\, f\left(\tfrac\right)+2\, f\left(\tfrac\right)+2\, f\left(\tfrac<3>\right)+f(1)\big) \\[5pt]

&=\tfrac\big(0+2⋅\tfrac+2⋅\tfrac+2⋅\tfrac+1\big) \\[5pt] &=\frac \end\]

Exercise \(\PageIndex<2>\) Use the trapezoidal rule with \( n=2\) to estimate \(\displaystyle ∫^2_1\frac\,dx.\) Hint Set \(Δx=\dfrac<2>.\) The endpoints of the subintervals are the elements of the set \(P=\left\<2>,2\right\>.\) Answer \(\dfrac\)

An important aspect of using these numerical approximation rules consists of calculating the error in using them for estimating the value of a definite integral. We first need to define absolute error and relative error.

Definition: absolute and relative error If \(B\) is our estimate of some quantity having an actual value of \(A\), then the absolute error is given by \(|A−B|\). The relative error is the error as a percentage of the actual value and is given by \[\left\lvert\frac\right\rvert⋅100\%.\]

Example \(\PageIndex<4>\): Calculating Error in the Midpoint Rule Calculate the absolute and relative error in the estimate of \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^2\,dx\) using the midpoint rule, found in Example \(\PageIndex\). Solution: The calculated value is \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^2\,dx=\frac\) and our estimate from the example is \(M_4=\frac\). Thus, the absolute error is given by \(\left\lvert\frac−\frac\right\rvert=\frac≈0.0052.\) The relative error is \[\frac=\frac≈0.015625≈1.6\%.\nonumber\]

Example \(\PageIndex<5>\): Calculating Error in the Trapezoidal Rule Calculate the absolute and relative error in the estimate of \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^2\,dx\) using the trapezoidal rule, found in Example \(\PageIndex\). Solution: The calculated value is \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^2\,dx=\frac\) and our estimate from the example is \(T_4=\frac\). Thus, the absolute error is given by \(\left\lvert\frac−\frac\right\rvert=\frac≈0.0104.\) The relative error is given by \[\frac=0.03125≈3.1\%.\nonumber\]

Exercise \(\PageIndex<3>\) In an earlier checkpoint, we estimated \(\displaystyle ∫^2_1\frac\,dx\) to be \(\frac\) using \(T_2\). The actual value of this integral is \(\ln 2\). Using \(\frac≈0.6857\) and \(\ln 2≈0.6931,\) calculate the absolute error and the relative error. Hint Use the previous examples as a guide. Answer absolute error \(\approx 0.0074,\) and relative error \(\approx 1.1\%\)

In the two previous examples, we were able to compare our estimate of an integral with the actual value of the integral; however, we do not typically have this luxury. In general, if we are approximating an integral, we are doing so because we cannot compute the exact value of the integral itself easily. Therefore, it is often helpful to be able to determine an upper bound for the error in an approximation of an integral. The following theorem provides error bounds for the midpoint and trapezoidal rules. The theorem is stated without proof.

Error Bounds for the Midpoint and Trapezoidal Rules Let \(f(x)\) be a continuous function over \([a,b]\), having a second derivative \(f''(x)\) over this interval. If \(M\) is the maximum value of \(|f''(x)|\) over \([a,b]\), then the upper bounds for the error in using \(M_n\) and \(T_n\) to estimate \(\displaystyle ∫^b_af(x)\,dx\) are \[\text

We can use these bounds to determine the value of \(n\) necessary to guarantee that the error in an estimate is less than a specified value.

Example \(\displaystyle \PageIndex<6>\): Determining the Number of Intervals to Use What value of \(n\) should be used to guarantee that an estimate of \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0e^\,dx\)is accurate to within \(0.01\) if we use the midpoint rule? Solution We begin by determining the value of \(M\), the maximum value of \( |f''(x)|\) over \( [0,1]\) for \( f(x)=e^\). Since \( f′(x)=2xe^,\) we have \[ f''(x)=2e^+4x^2e^.\nonumber\] Thus, \[ |f''(x)|=2e^(1+2x^2)≤2⋅e⋅3=6e.\nonumber\] From the error-bound Equation, we have \[ \text\, M_n≤\frac≤\frac=\frac.\nonumber\] Now we solve the following inequality for \(n\): \[\frac≤0.01.\nonumber\] Thus, \(n≥\sqrt>≈8.24.\) Since \(n\) must be an integer satisfying this inequality, a choice of \(n=9\) would guarantee that \[ \left\lvert ∫^1_0e^\,dx−M_n \right\rvert

Exercise \(\PageIndex<4>\) Use Equation to find an upper bound for the error in using \(M_4\) to estimate \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^2\,dx.\) Hint \(f''(x)=2,\) so \(M=2.\) Answer \(\dfrac\)

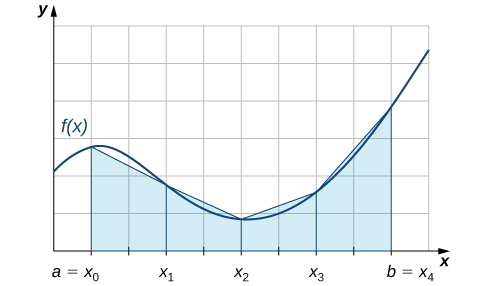

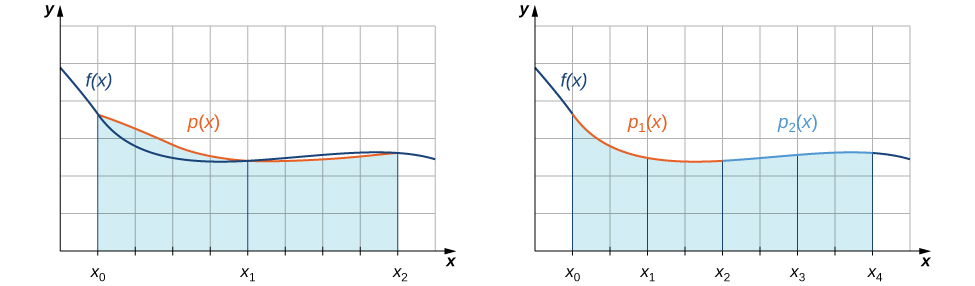

With the midpoint rule, we estimated areas of regions under curves by using rectangles. In a sense, we approximated the curve with piecewise constant functions. With the trapezoidal rule, we approximated the curve by using piecewise linear functions. What if we were, instead, to approximate a curve using piecewise quadratic functions? With Simpson’s rule, we do just this. We partition the interval into an even number of subintervals, each of equal width. Over the first pair of subintervals we approximate \(\displaystyle ∫^_f(x)\,dx\) with \(\displaystyle ∫^_p(x)\,dx\), where \(p(x)=Ax^2+Bx+C\) is the quadratic function passing through \((x_0,f(x_0)), \,(x_1,f(x_1)),\) and \((x_2,f(x_2))\) (Figure \(\PageIndex\)). Over the next pair of subintervals we approximate \(\displaystyle ∫^_f(x)\,dx\) with the integral of another quadratic function passing through \( (x_2,f(x_2)), \,(x_3,f(x_3)),\) and \((x_4,f(x_4)).\) This process is continued with each successive pair of subintervals. To understand the formula that we obtain for Simpson’s rule, we begin by deriving a formula for this approximation over the first two subintervals. As we go through the derivation, we need to keep in mind the following relationships: \[f(x_0)=p(x_0)=Ax_0^2+Bx_0+C\] \[f(x_1)=p(x_1)=Ax_1^2+Bx_1+C\] \[f(x_2)=p(x_2)=Ax_2^2+Bx_2+C\] \(x_2−x_0=2Δx\), where \(Δx\) is the length of a subinterval. \(x_2+x_0=2x_1,\) since \(x_1=\dfrac\). Thus, \[\begin ∫^_f(x)\,dx&≈∫^_p(x)\,dx \\[5pt]

&=∫^_(Ax^2+Bx+C)dx \\[5pt]

&=\left(\fracx^3+\fracx^2+Cx\right)\bigg|^_ & & \text \\[5pt]

&=\frac(x_2^3−x_0^3)+\frac(x_2^2−x_0^2)+C(x_2−x_0) & & \text \\[5pt]

&=\frac(x_2−x_0)(x_2^2+x_2x_0+x_0^2)+\frac(x_2−x_0)(x_2+x_0)+C(x_2−x_0) \\[5pt]

&=\frac\bigg(2A(x_2^2+x_2x_0+x_0^2)+3B(x_2+x_0)+6C\bigg) & & \text\, \frac. \\[5pt]

&=\frac\bigg((Ax_2^2+Bx_2+C)+(Ax_0^2+Bx_0+C)+A(x_2^2+2x_2x_0+x_0^2)+2B(x_2+x_0)+4C\bigg) & & \text \enspace Δx = \frac \\[5pt]

&=\frac\big(f(x_2)+f(x_0)+A(x_2+x_0)^2+2B(x_2+x_0)+4C\big) & & \text \\[5pt]

& & &\quad f(x_2)=Ax_2^2+Bx_2+C \enspace \text \enspace f(x_0)=Ax_0^2+Bx_0+C. \\[5pt]

&=\frac\big(f(x_2)+f(x_0)+A(2x_1)^2+2B(2x_1)+4C\big) & & \text\, x_2+x_0=2x_1. \\[5pt]

& & &\quad\text\, x_1 = \frac, \enspace \text \\[5pt]

&=\frac\big(f(x_2)+4f(x_1)+f(x_0)\big). & & \text \, f(x_1)=Ax_1^2+Bx_1+C. \end\] If we approximate \(\displaystyle ∫^_f(x)\,dx\) using the same method, we see that we have \[∫^_f(x)\,dx≈\frac(f(x_4)+4\,f(x_3)+f(x_2)).\nonumber\] Combining these two approximations, we get \[∫^_f(x)\,dx=\frac(f(x_0)+4\,f(x_1)+2\,f(x_2)+4\,f(x_3)+f(x_4)).\nonumber\] The pattern continues as we add pairs of subintervals to our approximation. The general rule may be stated as follows.

Simpson’s Rule Assume that \(f(x)\) is continuous over \([a,b]\). Let \(n\) be a positive even integer and \(Δx=\dfrac

Just as the trapezoidal rule is the average of the left-hand and right-hand rules for estimating definite integrals, Simpson’s rule may be obtained from the midpoint and trapezoidal rules by using a weighted average. It can be shown that \(S_<2n>=(\dfrac)M_n+(\dfrac)T_n\). It is also possible to put a bound on the error when using Simpson’s rule to approximate a definite integral. The bound in the error is given by the following rule:

Rule: Error Bound for Simpson’s Rule Let \(f(x)\) be a continuous function over \([a,b]\) having a fourth derivative, \( f^(x)\), over this interval. If \(M\) is the maximum value of \(∣f^(x)∣\) over \([a,b]\), then the upper bound for the error in using \(S_n\) to estimate \(\displaystyle ∫^b_af(x)\,dx\) is given by \[\text\, S_n≤\frac.\]

Example \(\displaystyle \PageIndex<7>\): Applying Simpson’s Rule 1 Use \(S_2\) to approximate \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^3\,dx\). Estimate a bound for the error in \(\S_2\). Solution Since \([0,1]\) is divided into two intervals, each subinterval has length \(Δx=\frac=\frac\). The endpoints of these subintervals are \(\left\<0,\frac,1\right\>\). If we set \(f(x)=x^3,\) then \[S_4=\frac⋅\frac(f(0)+4\,f(\frac)+f(1))=\frac(0+4⋅\frac+1)=\frac.\nonumber\] Since \( f^(x)=0\) and consequently \(M=0,\) we see that Error in \(S_2≤\frac=0.\) This bound indicates that the value obtained through Simpson’s rule is exact. A quick check will verify that, in fact, \(\displaystyle ∫^1_0x^3\,dx=\frac.\)

Example \(\displaystyle \PageIndex<8>\): Applying Simpson’s Rule 2 Use \(S_6\) to estimate the length of the curve \(y=\fracx^2\) over \([1,4].\) Solution The length of \(y=\fracx^2\) over \([1,4]\) is \(\displaystyle ∫^4_1\sqrt\,dx\). If we divide \([1,4]\) into six subintervals, then each subinterval has length \(Δx=\frac=\frac\), and the endpoints of the subintervals are \( \left\,2,\frac,3,\frac,4\right\>.\) Setting \( f(x)=\sqrt\), \[S_6=\frac⋅\frac(f(1)+4f(\frac)+2f(2)+4f(\frac)+2f(3)+4f(\frac)+f(4)).\nonumber\] After substituting, we have \[S_6=\frac(1.4142+4⋅1.80278+2⋅2.23607+4⋅2.69258+2⋅3.16228+4⋅3.64005+4.12311)≈8.14594\,\text.\]

Exercise \(\PageIndex<5>\) Use \(S_2\) to estimate \(\displaystyle ∫^2_1\frac\,dx.\) Hint \[S_2=(\fracΔx(f(x_0)+4f(x_1)+f(x_2))\] Answer \(\frac\)